Memorial

Patrick Garland

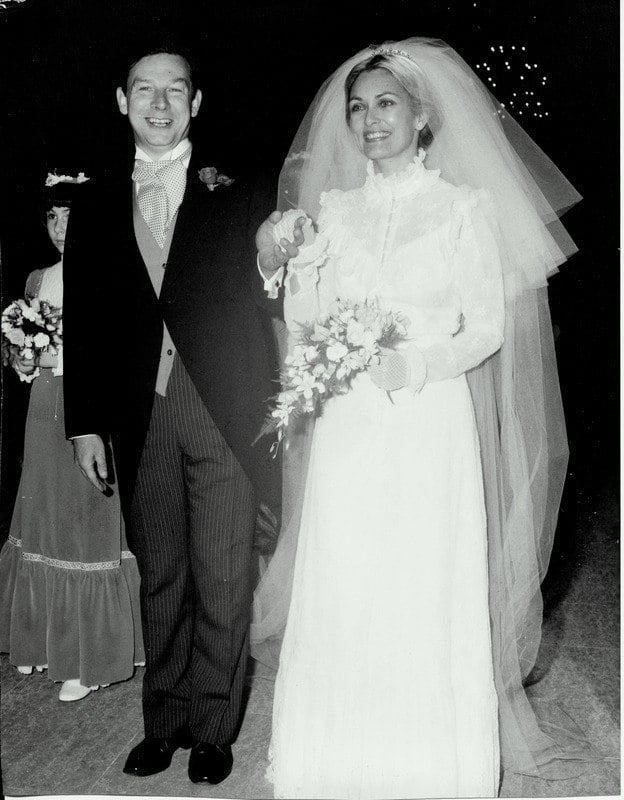

My husband Patrick Garland died 19th April 2013 after a long illness which he bore with great fortitude. It was thanks to his support and generosity that the ABC Animal Sanctuary Charity was founded on our land and it ensures that the resident unwanted animals have a home for life and that the charity is able to continue its excellent work of rescuing, rehabilitating and rehoming forever.

He had been a brilliant theatre and film director - at the time we met he had four plays running in the West End at the same time - and ran the Chichester Festival Theatre for 10 years with immense success both staying financially solvent without grants and directing innumerable hit shows.

He brought much pleasure to a great number of people. He was the kindest, most charming, most informed, most generous and wittiest of people. He had a collection of 6000 books and knew them all. He will be much missed by me and the family and his close friends.

Alexandra Bastedo

VIDEO Stars pay tribute to Patrick Garland at Chichester Cathedral ... A host of stars from stage and screen gathered at Chichester Cathedal for a service of thanksgiving

for the life of theatrical great Patrick Garland. www.bognor.co.uk/.../video-stars-pay-tribute-to-patrick-garla...

A Eulogy for Patrick Garland by Simon Callow

The death of a close friend is always a fell blow, but never more so than when that friend is someone one with whom one had laughed inordinately. When I heard the news about Patrick, the first words that came into my mind were those famously uttered by Dr. Johnson on the decease of his friend and former pupil David Garrick: “I am disappointed,” said Johnson, “ by that stroke of death that has eclipsed the gaiety of nations and impoverished the public stock of harmless pleasure.” Patrick Garland was a man of extraordinary cultivation and accomplishment, as poet, biographer, adaptor, director, producer, artistic director, interviewer, and master of ceremonies; his achievements in all these spheres fill pages and pages of Who’s Who, and appear in such profusion on the back of the programmes you hold in your hands, the record of a man and an artist of astonishing versatility and prodigious energy. But for all of us who were lucky enough to know him personally his outstanding quality, beyond all the brilliance and imagination and inventiveness was a sweetness and joyous enthusiasm with which he irradiated any life he touched. He possessed to a marked degree those qualities for which we seem to need to reach for the French language – joie de vivre, élan vital, bonhomie. He was as English as the English Hymn book, but it seems natural in talking about him to reach for those Gallicisms which he scattered about so liberally in his own conversation.

It was National Service which took him to France, starting his long love-affair with the country and its language; it also, he told me, made a democrat of him, introducing him to people outside his own comfortable middle-class background, breeding in him a lifelong fascination with everyone and everything. He was an avid connoisseur of people’s foibles and follies, their quirky turns of phrase, their physical eccentricities and their sudden shafts of profundity. Like Eliza Doolitle, he could do you anyone after five minutes in their company. His wonderfully mobile features, his infallible ear, his ability to give himself over to another person, would deliver you a whole life in a few phrases.

I first came across Patrick’s name as the director/adaptor of a treasurable BBC 2 series – unimaginable today – called Six Great Gossips. Alan Bennett played Augustus Hare, Alan Badel Oscar Wilde, and Roy Dotrice John Aubrey; the Aubrey episode took on a life of its own as Brief Lives, in the West End and on Broadway. The success of the series was no accident. Patrick was himself a great gossip, but that unusual thing, a gossip entirely without malice. There was about him a sweetness of disposition, an essential amiability, which informed all of his work, but which in the end probably denied him the biggest prizes, for which a degree of ruthlessness entirely alien to him is the sine qua non. He was too interested in relishing the passing moment to focus on the future. The sheer pleasure of being alive was what possessed him. We didn’t meet till the 1990’s, quite late in his career; when we did, we immediately plunged into a bubble bath of anecdote which didn’t let up till the last time I saw him, towards the end of last year. His frailty was unmistakeable by then, but the twinkle was still in the eye; his nostrils literally flared at the scent of an indiscretion, he would still throw his head back with delight on hearing the latest outrageous mot. He even had new naughtinesses for me, though how he got hold of them in deepest Sussex is a wonder: he was to the end switchboard central, the bush telegraph, for news of the passing parade of mankind. This was life to him; this was how he understood the human comedy.

He was the Goncourt Brothers rolled into one, observing, analysing, crystallising the passing scene, but unlike them he had a brilliant career of his own, an extraordinary one, like no other, in fact. It encompassed early days as a penetrating interviewer and maker of television documentaries alongside Ken Russell and Jonathan Miller on Huw Wheldon’s Monitor, as well as directing Alan Bennett’s dazzling and now criminally erased sketch programme On the Margin, before being responsible Bennett’s early playwriting triumphs, Forty Years On and Getting On. There was a Cyrano at the National, brilliantly adapted by him with reference to the verse of John Suckling. There were two record-breaking stints as director of the Chichester Festival, several musicals, and a superb adaptation of Hardy’s Under the Greenwood Tree, award-winning films, including A Doll’s House with Clare Bloom. At one time he had four plays running simultaneously in the West End, another record. He also helmed great public occasions like the Investiture of the Prince of Wales at Caernarvon Castle and the State Funeral of Sir Laurence Olivier. At the other end of the scale were the smaller pieces on which he worked with Roy Dotrice, with Alec McCowen, with Eileen Atkins and with Vanessa Redgrave, often adapting, always editing and shaping; as a director, he was the perfect audience, an infallible guide to what was working and what wasn’t.

All of this, he enjoyed inordinately. Success impinged on him only in so far as it gave him more and more opportunities to do what he most loved. There was nothing grand, nothing pompous, nothing smug about him: he loved actors, he loved writers, he loved designers, he loved the theatre, and he spread this love around him. He was a master raconteur with a wonderful power of mimicry and perfect timing, his relish in telling the tale culminating in unsuppressible explosions of laughter. He and I worked together on many shows, and it was always rehearsal by anecdote – a much underrated rehearsal technique, in my view – filling the room with wit and fun and good will and, as often as not, unexpected illumination. Patrick had in his repertory the anecdote scurrilous, the anecdote historic, the anecdote surreal, the anecdote instructive. His knowledge of literature, of theatre, of painting and of music were non-pareil: he consumed books, records and plays as if they were so many delicious cakes. (He also consumed a great many delicious cakes). The past, and the characters of literature, were every bit as alive to him as the present and real people. He was not – despite a memorable appearance in pink shirt and floppy hair and incipient sideburns in his famous 1965 television interview with Noël Coward, and notwithstanding his fascination with everything new – a particularly modern man: technology left him indifferent and often baffled. When his adoring staff wanted to mark his departure after a second brilliantly successful tenure at Chichester, they presented him with a mobile telephone. Patrick, the master of the seamless impromptu speech, was for once genuinely lost for words, until he blurted out: “But what will I do with it?”

It was the personal, the human, that he valued above all else. He was, in fact, to use yet another French phrase, un homme moyen sensuel; as Oscar Wilde said of himself, quoting Gauthier, he was one for whom the world of the senses was all important. He loved life – his loved his life. Above all, perhaps, he loved his friends. He was greatly attached to the church; he was a believer, and he revelled in its language, its music and its rituals. But I think it would be correct to say that his true faith was friendship. It was his lifeblood, his constant study, his supreme gift. He practiced it on the page, down the telephone line, over breakfast, over lunch; over tea, over supper. Nothing was too much to do for a friend. Many were the charming presents which would arrive out of the blue, the postcards reporting something just heard or just read, the sudden impulsive expressions of affection. “I am so fond of you, my dear,” he would write, for no other reason than that it was true. His favourite phrase from Dickens was Joe Gargery’s “Ever the best of friends, eh, Pip?” That and the same character’s immortal effusion: “Wot larks, Pip! Wot larks.”

Alongside friendship was the love of beautiful women. There were many of them, but the most beautiful of all, the absolute centre of his life, was Alexandra, serene, witty, strong; during these last difficult years, she became his rock, his comfort, his salvation. Again and again he spoke, with something like bewilderment, of how much he loved her, of how much he owed her, of how inconceivable life would be without her. His great friend Keith Baxter saw him only hours before he died. He was sitting up in a chair, very frail but beautifully dressed, and as Keith left Patrick kissed him and said “I’m fighting back Keith, I’m fighting back” and then he said “I love Alexandra so much.”

Thank God for her: the last few years were hellish for Patrick, the great golden circle of warmth dimmed and diminished, his joy in work and his essential gregariousness circumscribed. But the sweetness and the enthusiasm never flagged. Right up to the end, we were delightedly celebrating Dickens, finding new things in his work; The Mystery of Charles Dickens and Dr Marigold and Mr Chops were the fruit of our shared passion for him. He knew the entire oeuvre intimately; for him the characters were personal acquaintances, and he would delightedly quote them as if he’d just bumped into them on the stairs. Above all, he loved the comedy and the pathos. He acknowledged, with awe and admiration, the terrible blackness at the heart of Dickens, but Patrick was for the light, not for the dark. When we started work on The Mystery of Charles Dickens, he said that he was as convinced as anything he’d ever been convinced of that the play must end with the ineffable passage towards the end of the book where the author takes leave of Pickwick. It was a show which went through many metamorphoses, but Patrick’s infallible instinct had not failed him: whatever else in the piece changed, this was how it always ended, leaving the audience elevated and exalted. It seems to me that it sums up, if anything could, what Patrick Garland was all about:

And there in the midst of all this, stood Mr. Pickwick. Let us leave our old friend in one of those moments of unmixed happiness, of which, if we seek them, there are ever some, to cheer our transitory existence here. There are dark shadows on the earth but its lights are stronger in the contrast. Some men, like bats or owls, have better eyes for the darkness than for the light; we, who have no such optical powers, are better pleased to take our last parting look at our imaginary companions, when the brief sunshine of the world is blazing full upon them.